By Jack Sagar.

When I was seven, I used to imagine my father at the end of the street. He would be standing under the lamppost, by the tree I thought looked like a phoenix, just waiting for me to reach him. It began as a way of tricking myself into running faster — just picture your dad at the end of the street, I thought to myself — but then it seemed to become a genuine yearning. I would reach the lampost, struggling to catch myself against it, just for his image to disappear as quietly as it had arrived.

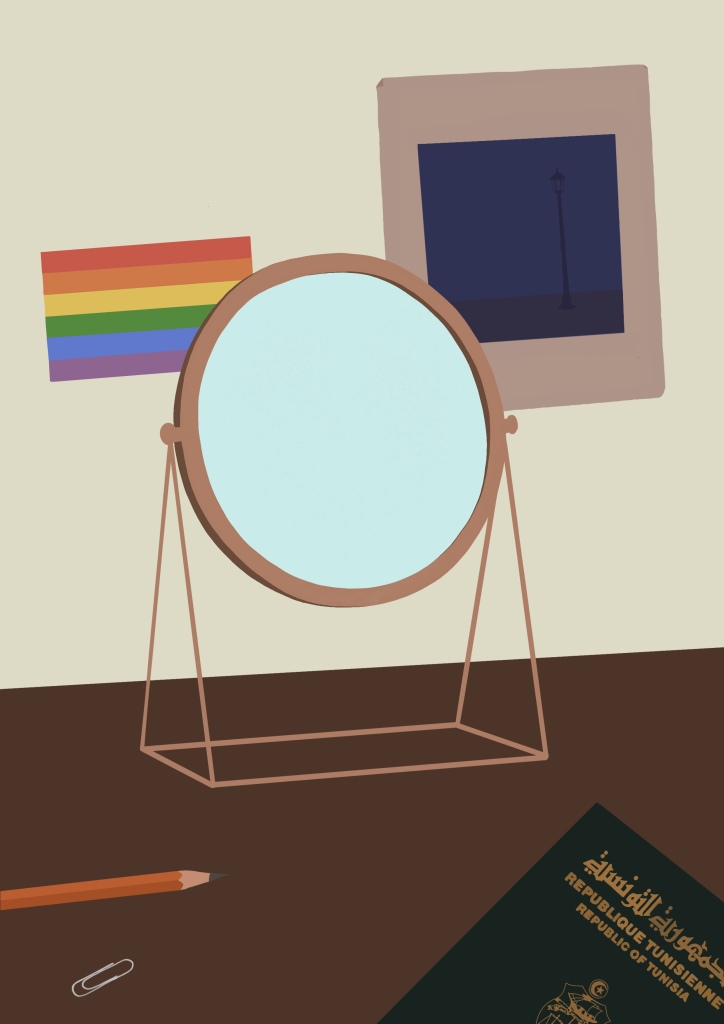

I might have stopped running, and imagining my father to be where he simply wasn’t, but I did not stop thinking about him. Where was he? — my mother, by no fault of her own, did not really know. ‘Somewhere near Tunis,’ she would hazard a guess. Their love had unfolded from 1996 to 1998 — my auntie, with my mum, making the most of the perks of being a travel agent, took trips to Tunisia every other month. This was a time when the Tunisian state was negotiating its identity with the forces of emerging feminist voices, both of which were resistant to rising Islamic fundamentalism within Tunisia. I’d like to think that my mother grappled with the complexities of the Tunisia she found herself and my father in, the one which made their relationship possible. But I suspect my mother knew what my father thought, and I gather that his politics was unsurprising given his age — my father, with a contrarian ‘free spirit’ which looked a lot like my auntie’s youthful love of the cheap wine.

But it is 1998 and I am born. I come crashing into the world in the back of a taxi, a full head of jet black hair appearing after a birth just short of 40 minutes. ‘Jack’ was the most popular name of the year, and Google was to be ‘born’ less than two weeks after. I cannot know exactly what happened, but it was a mutual decision that I would not see my father until I was 18. It was better for me that way — he would write, until he wouldn’t, and the countdown would begin. We would usher a new millennium and a new decade atop of that long before my father and I spoke for the first time.

I had always looked for him online, mainly on Facebook. I would try his first name followed by his surname and I would try it the other way around. My mum would try too. I always hoped he would find me. Two months after my 18th birthday, whilst complaining about boy troubles over the phone to a friend, I would receive a Facebook notification from an account named ‘Ang Ang’. The small icon beside the name was enough for me to know: my father had sent me a friend request. We had such similar faces. I would soon learn that ‘Ang Ang’ was a nickname — Angel, Angel, his friends call him.

***

Anglophone philosophical answers to questions about race and identity — questions which this tradition has spent most of its time neglecting — are broadly criteriological. They attempt to isolate the necessary and sufficient criteria under which one must ‘fall’ to be a woman or non-white, for instance. But my identity is not a cluster of properties I bear like those concrete, intrinsic properties, height or eye colour. My identity has a history, one in which my inquiry and perspective on is not ‘detached’ but immersed. I am part of the history as it unfolds. Whatever I say today becomes my history eventually; whatever I am eventually will be a complicated product of it all. This is to say, my identity is not some ahistorical fact for which we can develop logical checkboxes; it is history unfolding, whether I look at that history or ignore it.

This is not to say that we don’t all, on an everyday basis, apply a rough set of (explicit or implicit) criteria to judge whether an individual belongs to a given identity group. To some degree, the development of these principles regarding identity does protective work. It defends the boundaries and realities of those who may not be in the best position to protect themselves alone. It allows us to distribute our trust and resources, as well as reminds us whose voice to trust more than others on particular matters — standpoint epistemology shows that people have epistemic privileges in virtue of their being part of a particular social group. What I am resisting, however, is a theorist’s localisation of authority — epistemic and moral — to the academy, or the Tunisians in Tunisia. That it would be morally as well as epistemically invalid for me to say ‘I am Tunisian’ does not seem to me the right result.

I am asking the question of whether I can ‘become’ Tunisian — can I go to Tunisia, engage with its culture, make friends in the place of family, learn Arabic as my parents had already intended for me? This, to some of my friends, is a clear-cut issue. Your father is Tunisian; you are Tunisian — there is nothing suspicious about your desire to embrace your Tunisian heritage. Other friends, when I have mentioned wanting to attend more BAME events in college and university, have rolled their eyes at me. I am white-passing, culturally white. I suppose the worry is that I am as ethically dubious as the ‘transracial’ Rachel Dolezal. But the deeper question is: Is it my right to ask and to answer?

As Amia Srinivasan recently told the Financial Times, when you can solve philosophical problems it can be tempting to approach all problems that way. Her reservation, however, is that not all problems take that ‘shape’. Here, I find inspiration for a couple of points. The first, alongside the question of anyone’s personal identity, is a question of the identity of philosophy or the philosopher. There are those for whom philosophy is a science, like mathematics or physics, whereby applying the methods of logic and conceptual analysis will produce determinate answers. And there are those for whom philosophy was about asking the important questions, not to find answers exactly but a certain sort of authenticity through applying doubt, irony, phenomenology, dialectics.

I myself am sympathetic to a sort of ‘pragmatism’ about truth. Unlike the analytic philosopher, if that title designates any specific person at all, I take the truth to be something we achieve in virtue of achieving a morally and politically better world — that what is ‘true’ is what we can be confident in when we have formed a world we want to be part of. This is not my qualm with Anglophone approaches to identity, although it may have helped me to see it — as did Srinivasan’s image of ‘shape’. I worry about their inability to make room for the personal dimension, or shape, of these questions of identity. A presentation of these criteria as picking out mind-independent features of the objective world is harmful to those who are unable to protect their identity, such that there is an answer of who we are independent of who we take ourselves to be. One needn’t be a pragmatist of sorts to take this line, but it ties the truth of who you are to your ‘truest’ self — which is, I take it to be, about who you would most like to become.

There is a slight degree of truth to this independence principle. Someone like Dolezal, I suspect, can never make up for what isn’t there in her history. Were my father not Tunisian and were I not raised by my mother on the premise I would one day learn Arabic and go to Tunisia and be united with my whole family, I would not have a leg to stand on. But these things did happen, and how I relate to them is, to some degree, my prerogative. It is not that I am making claims in a vacuum — even though I have been trained in analytic philosophy. Nor would my claims transcend their context had I been raised in Tunisia. But to think that we have reached such a vacuum, I suspect, gives rise to a second worry. These approaches to identity are alienating to those for whom identity is a real psychological challenge.

I say this as someone with two diagnosed mental health conditions — not exactly psychically separable, but diagnostically so — that makes identity problematic. I am talking really about the dissociative, as well as the obsessive-compulsive. This is the point at which the intentional structure of self and of world degrade and, in touch with broadening possibilities, one’s entire being is a difficult question. To be a difficult question brings with it all-consuming anxieties, like whether one’s asking of questions or making of claims lacks a certain sort of right, a certain sort of innocence. Other extant things — each of which you struggle to bring clearly into view — feel to be a reminder of just how mad, bad, and dangerous you are. If only you could be something else? It reminds me of the worry that Srinivasan shared with the Oxford Review of Books for how vulnerable people can lose their knowledge when met by a skeptical representative of those in a greater position of power. Not only must tutors responsibly wield their power in relation to vulnerable students when they dismiss or demean their work, philosophers must become more sensitive to how metaphilosophical norms make not only certain thoughts but certain identities harder to express. I have wanted to give up on my heritage for what I wanted to call ‘philosophical’ concerns. For those concerned with the interplay between the political and pedagogical should also be painstakingly aware of the relationship between oppression and psychological trauma. My mental health conditions did not appear in a vacuum either.

My father and I did not maintain a relationship for long. As I’ve spent 1700 words saying, identity is complicated — he could accept me as his son, he said, only if I would pray to keep my homosexuality at bay. I told him this was an ultimatum he could not win, and I cut connection seconds later. But I am not a liminal case, a difficult question, because I find myself at an intersection; nor am I a liminal case, a difficult question, because I have not crossed everyone’s mind. I am a reasonable answer to a question with a shape of many edges, many dimensions, a question that I have asked. I am gay; I am young; I am mentally ill; I am naive; I am not a philosopher (though I might like to be); and I am, after all, a Tunisian man.